Andrew Vidgen: Moments #2

- Alan Humm

- Apr 29, 2021

- 2 min read

I am six years old. I am hurrying, with my mother and my step-dad, John, towards the train station. John carries our clothes in a borrowed suitcase and my mother is holding my sister close to her breast. She is still producing milk. This is an escape from our home town. We wait for the train on an empty platform until the tracks begin to whisper and the train approaches. On board, I watch the Clyde and Park Lea Fields, where I once writhed, sunburnt, in a tent. Joan will be waiting, to harbour us.

We are in Joan's house. The adults are playing cards. In a near room we huddle on the mattress on the floor. Children giggle and wriggle beside me. The card game has a rhythm: pauses for still faces; sighs; and victorious shouts. Joan's husband can raise up ghosts. They are in communion now: they call up the departed like they're in a fairground séance. And then they come. They're coy at first, like children. They fill the room with titular claims, some ordinary and others grand. I move from the bed and stand in the hall. Through the door I hear, "You look after her John".

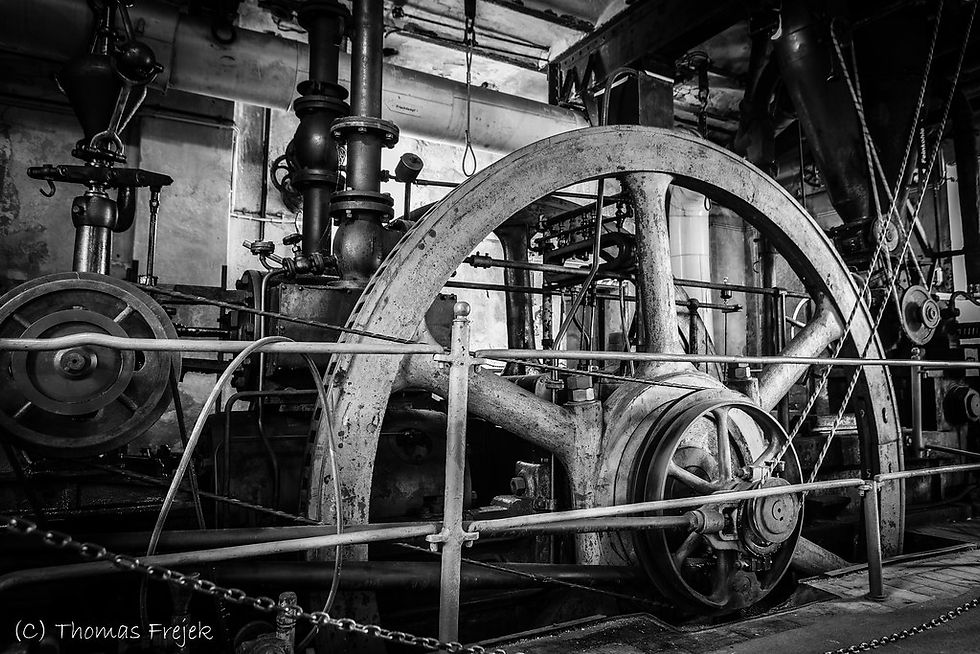

We have arrived in Pat's house in Largoward, where she lives alone with her two sons. We sit around the dinner table and they talk about working together, as cleaners, in the Star Hotel and the Hydro. They talk about Pat's husband, Ian, dying after being pulled into a machine in his factory. I imagine Ian, in overalls. I imagine the cogs; the way they screech and grind. I hear them say that the machine pulled him in, and I see his sleeve become ensnared; his panicked tugs and screams. The monster devours him then stops with a satisfied hiss. I look down at my dinner. It's mince and potatoes. My stomach turns.

I am seven years old. We have moved back to my home town. We are staying with my widowed uncle. Up and down the street, the men sleep drunkenly and, when roused, they shout at the women and bark at their children. My uncle is no different. While he is sleeping, I tie up his feet with string and unfurl the ball, out of the living room, down the hall and into the garden. I secure my string to the holly bush so that when he wakes he will fall, dishonourably. I wait. The string tugs in anxious expectancy, then quivers to rest. I look up and Michelle is there. My look betrays my love. She blows then pops her bubble gum. She pinches the gum, stretches it out as far as it will go and then, with a flick of her hand, capably furrows it around her finger before placing it back in her mouth. With her teeth, she gnaws the remnants from her finger. I am torn between Michelle and my booby trap. The bush calls my attention with a hopeful shudder. When I look up, Michelle has gone.

Andrew Vidgen is a psychologist and musician. From time to time he excavates himself to find things to write down. These pieces are from a larger collection of moments from his life

Comments